Develop Your Game Design Skills Using Paper Prototypes

You don’t have to dive straight into Unreal Engine 4 or Unity 3D to start practising your game design skills.

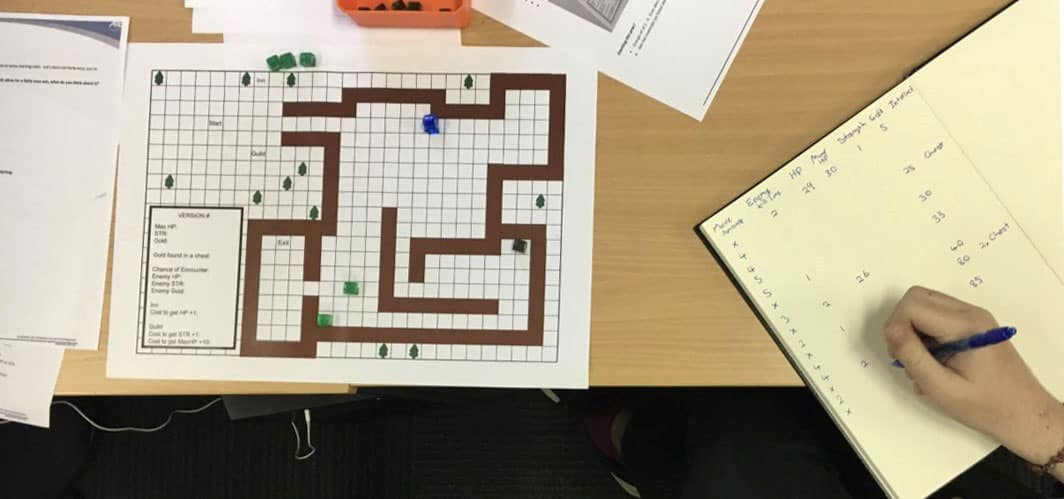

Making a prototype in a game engine is great but sometimes it can be much quicker to go from initial concept to test and iteration on a game idea with pencils, paper, dice and random board game pieces. This is known as paper prototyping.

Many developers use paper prototyping to experiment with an idea before going anywhere near a game engine. Prototypes are an invaluable way for designers to gain feedback on an idea before investing too much time, art or programming resources, only to find out the idea is not engaging, doesn’t work or isn’t worth pursuing.

If you are looking to build a portfolio to get into AIE’s Game Design and Production two-year program, a paper prototype is a great way to show you are thinking about the player experience.

This guide to paper prototyping will cover the following:

- What is a game mechanic?

- Examples of paper prototyping

- Creating the rules for your game

- Playtesting

- Building your design portfolio

Let’s dive in and start your paper prototyping journey.

What is a game mechanic

First thing we are going to need to understand are game mechanics.

Mechanics are the base components of the game - its rules, every basic action the player can take in the game, etc. They are things like, Mario’s jump, the boost in Rocket League, honking in Untitled Goose Game and needing to keep your Sim’s fed.

Try having a quick think about your favorite game and list the first 5 game mechanics that come to mind.

Examples of paper prototyping

Now that you have some game mechanics in mind, the next step start thinking about how you could prototype them, without using a computer. There is no set way to do this. Feel free to use whatever make sense for the mechanic you are wanting to prototype. Here are a few examples to get you started.

Weapon Accuracy

With a 6-sided die you have a 1 in 6 chance of getting the desired number (hitting the target). Want to be less accurate? A 20-sided die will make it a lot harder to get the number you want.

Procedural Level Generation

Want to make a level where each playthrough is different? Create a bunch of premade level piece’s on cards and then shuffle the deck. Each time you flip a card over the level will be different. Board games like Catan use this.

Player Movement Speed

Assigning movement speed values to a character can allow you to decide which characters to move at the beginning of a turn and which would move last. While turn based games like Pokemon use this, you can also use it to prototype out First Person Shooter or racing game. Bigger/ slower characters might only move 3 places instead of 4. Just remember to provide some incentive or benefit to having a slower character (can you think of any?).

RPG Inventory

You can create an inventory system for an RPG with limited space by assigning values to different cards and only allowing a player to hold up to a max number you decide. Now a player can only carry up to a certain ‘weight’ and must decide which items are the most valuable.

What ways can you think to paper prototype two of the game mechanics from your favourite game?

Creating the rules for your game

Now it’s time to start putting what you have learnt into your own prototype.

To help get you started we have included some print outs that you can use. Try using just one or mix and match them. Need a piece that you don’t see in what we have provided? That’s ok, make it or find something within arm's reach and use that.

- Blank_Cards_3x5

- Character_Sheet_Board_Game

- Graph Paper Half Inch

- Hex_Cards 22

- Hexagon Portrait Letter

Have a look at the pieces and think about what kind of game you could make.

- Is the goal to have the most of something or get rid of all of them?

- Are players working together or against each other?

- What things can the player do on their turn?

- Are there even turns, or does everyone make an action at the same time?

- How do you counter powerful pieces?

- Are their multiple ways to win?

- Does your game even need a winner and loser?

Write down the steps for playing the game. Don’t worry about trying to decide all the rules when you first start. Focus on the core mechanic using the list above. You can add on extra things later.

If you are unsure on how to use the pieces, go back to thinking about your favourite game for a moment. See how many different mechanics you can create from that using only the parts available in the link above.

Time to playtest

Now you have the basics down for your prototype, it’s time to playtest.

The quickest way to get started is to play against (or with, depending on your game) yourself. Try acting as different personalities, aggressive, defensive, the person that always tries to bend the rules. This will be a great way to see your game in action.

Once you have had a few games by yourself, make any changes that you need then collect the required number of players together and try playing through the game with them. This could be family or close friends.

Grab a notepad, you are going to want to write down a bunch of feedback as they play through your prototype.

- Do the rules make sense/ are they hard to explain?

- Is there anything the other players (or yourself) found unclear?

- Did they find the idea engaging?

- Which part of the game did they enjoy the most/ least?

- What questions are they asking you?

A huge benefit of paper prototyping is that if it isn’t going well you don’t need to rewrite any code, just let the other players know what you want to change, then play another round. Feel free to keep doing this until you have an experience that you enjoy. Make sure you write down all the rule changes for each playthrough, making note of what worked and what didn’t. Try writing your new ruleset concisely.

Now pass your game and its written rules onto someone who has never played it before and see what they think. Grab that trusty notepad again, it’s time to start making more observations. Can they follow your ruleset? Which parts are they unsure on? Try not to jump straight in and explain it unless they ask (and make note of what they are asking). Watching and listening to them try and figure out the rules is valuable feedback.

Observing people playing your game is a great way to see if they are trying any strategies you didn’t think of, or alternatively, is there a strategy or pieces they are not using at all? That might be an indication that it’s not understood, or the players don’t see it as a viable strategy.

It is through this iterative design process that you will begin to balance the design game. This iteration is why prototyping is so valuable.

I have a game, now what!

Congratulations you have just made a paper prototype.

This is something that you could use in your Portfolio Interview to get into our two year Game Design and Production program. We won’t have time to play through your game in your interview (unless it takes less than a few minutes) but we are keen to hear about it.

Create a short overview of your game and a more in-depth version where you explain the main rules. Bring in some photos, video or your written rules for the game. These will all help your interviewer learn about your game.

Something the teachers really like to see; you’re notes. How did the game evolve from your first playtest. Let us know what worked, what didn’t, and how your playtesting affected the finished game. Problem solving is a huge part of design and showing how you updated your design based on player feedback is great!

You are now ready to take the next big step towards your career as a Game Designer.

Apply Now for the next AIE Game Design intake.